By Robert Fisher-Hughes, AAP Columnist and Amateur Historian

By Robert Fisher-Hughes, AAP Columnist and Amateur Historian

It is often observed that America, settled by immigrants, is a nation composed of many nations. Even in its earliest days, this may have been truer of the colony of New Jersey than of most, and it is certainly very true of the State of New Jersey today. Yet among the colorful tapestry of nationalities comprising our state, some among the very earliest to settle in the area are also among the least remembered when numbering the members of our demographic panorama. This may be due to a variety of factors, such as an apparently seamless assimilation as the broader culture developed, but it nonetheless belies a surprising cultural diversity among identities rarely distinguished as unique today. One such national identity that settled early and with good fortune on the land of the future Township of Pennsauken was that of the Welshman, Griffith Morgan.

Wales is a distinct region of the island of Britain, inhabited since ancient times by a Celtic people related to the Scots, the Irish, and other Celtic peoples of Brittany, Cornwall, and the Isle of Man. Geographically, Wales is a little smaller than New Jersey, located on the west side of England, across the Irish Sea from Ireland. Wales is a land of mountains, valleys, and coastline. It was the rugged terrain of the landscape that probably accounted for the survival of the Welsh nation and so much of its culture, even after repeated wars with the Germanic Angles and Saxons, the Norman conquest, and even raids and incursions by Vikings and Irish pirates.

Wales retains a language all its own to this day, though it is rarely heard away from its home. Welsh culture is expressed first and foremost in its poetry, a pursuit descended from the bards of medieval times. National competitions in poetry known as Eistedfoddau continue to be held to this day. Welsh music is expressed in traditional choral competitions, but also in folk song, Welsh triple harp and even Welsh popular song. Festive celebrations of Welsh culture and music are known as Gymanfa Ganu.

Wales retains a language all its own to this day, though it is rarely heard away from its home. Welsh culture is expressed first and foremost in its poetry, a pursuit descended from the bards of medieval times. National competitions in poetry known as Eistedfoddau continue to be held to this day. Welsh music is expressed in traditional choral competitions, but also in folk song, Welsh triple harp and even Welsh popular song. Festive celebrations of Welsh culture and music are known as Gymanfa Ganu.

Wales also has its own, native patron saint, as Ireland has its Patrick and Scotland its Andrew. St. David was a medieval bishop whose simple piety is embodied in his reputed last words to his followers to “remember to do the little things you have seen me do.” St. David’s Day, March 1, is the national day of Wales, celebrated more widely each succeeding year.

Wales never achieved political unity, but was divided into numerous princedoms and clans. Eventually, the last native Welsh royalty to rule any part of Wales were defeated and killed by the forces of the English King Edward I in 1282. According to lore, in resolving the hostilities and assuring English rule, the tricky King Edward appeased Welsh national feelings by promising that Wales would be ruled by a prince who spoke not a word of the English language. He later presented that new “Prince of Wales” to the nation in the person of his own infant son, and thereafter the heir apparent to the English throne was the Prince of Wales.

Uprisings of the Welsh against English rule followed, and eventually Wales came to be dotted with formidable English castles, not to defend the Welsh but to defend the English rulers against the Welsh. Indeed, Wales today may have more castles for its size and population than any other nation in Europe.

The last great rebellion to challenge English rule, led by the Welsh hero Owain Glyndwr, came to its end by 1415, with Owain’s disappearance, neither crowned nor captured.

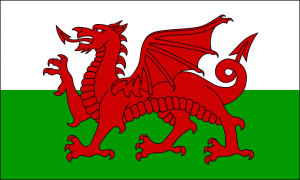

By Griffith Morgan’s time, Wales had become a distinct but vital part of the realm. Welsh soldiers served in English campaigns in France, Scotland, and Ireland, earning a reputation for courage, loyalty, and ability. According to one story, it was while serving the English crown in the Hundred Years’ War that Welsh archers, positioned in a French farmer’s leek field, placed leeks in their caps to distinguish friend from foe during the battle and thus created one of the most enduring of national symbols. To this day, Ireland’s shamrock and Scotland’s thistle have their counterpart in the Welsh leek. The other Welsh national symbol, the red dragon found on its flag, has origins that may date to ancient Rome.

The Tudor dynasty, which ruled England at the time of the discovery of America, was of partly Welsh ancestry crossed with the English House of Lancaster. Thus it was said that Wales at last conquered England. However, the Tudor King Henry VIII also incorporated Wales fully into the English state. He also brought the Reformation, establishing the Church of England in place of Roman Catholicism.

The Stuart dynasty of the 1600s eventually brought great turmoil to the kingdom, resulting in civil war between King and Parliament. During most of that war, Wales was largely supportive of the King. However, the war also brought about a whirlwind of social and religious change that affected England and Wales and also shaped the English colonization of America.

One of the religious sects that emerged from the turmoil was the Society of Friends, or Quakers, who had a strong presence in Wales as well as England. After the restoration of the crown, King Charles II arranged for the English colony of New Jersey to supplant the Dutch of New Netherlands. The English Lord Berkeley, who was a partner in the new colony with Sir George Carteret, eventually sold his interest and a group of Quakers soon undertook the colonization of West Jersey as a result, with promises of liberal terms of settlement and religious toleration.

English, Welsh, and Irish Quakers began to settle, bringing others with them as servants, laborers, and artisans necessary to modern life in the 17th Century. Dutch, Swedish and Finnish settlers were already thinly established along the Delaware River. African slaves were also brought, as the later, abolitionist views of the Quakers had not yet evolved.

The mariner Griffith Morgan was an early traveler to the new colonies. Pennsauken historian Jack Fichter believed he had successfully traced his background to the Welsh town of Haverford West and found evidence of Morgan’s religious dissent in court records of fines for failing to tithe and attend services of the Church of England, a common experience of the Quakers.

When the Morgan family settled itself on the banks of Pennsauken Creek in 1693, it joined many other Welsh families settling the Delaware Valley, including names like Lloyd, Thomas, Lewis, Williams, Jones, Evans, and Hughes. Successive waves of Welsh migration to the United States followed, populating towns and farms and ports and coal fields. Welsh Americans have been presidents, explorers, entrepreneurs, soldiers, artists, architects, and, of course, poets.

On Sunday, March 1, this year, the homestead of the Griffith Morgan family in Pennsauken will mark the occasion of St. David’s Day and share a historic heritage with its community. So come join us if you can! Cyfarchion Dydd Gwyl Dewii Bawb (St.David’s Day Greetings to Everyone)!