By Robert Fisher-Hughes, AAP Columnist and Amateur Historian

Ninety years ago, the first of two fatal train wrecks occurred near the same curve of track at Derousse Ave. in Delair. While the toll of this earlier accident was much less in terms of loss of life and injury, the response of the community was similar in both tragedies, evoking both shock and horror and a rising to the occasion that we would well remember to this day.

On April 8, 1926, the second section of the Nellie Bly left the tracks on the curve from the southbound tracks to the eastbound tracks; three people lost their lives, while as many as 170 were injured. While the wreck still smoldered at the site, blame was quickly placed on the engineer, who perished in the accident. Only months later, when the report of the Bureau of Safety of the Interstate Commerce Commission was complete, was the true cause of the accident made apparent.

The Nellie Bly, the fast train of the Pennsylvania Railroad between New York and Atlantic City, ran south along the line of the old Camden & Amboy line through Palmyra and Pennsauken, until it approached the east-west tracks that crossed the Delair railroad bridge. Here, a switch brought the trains onto a left curve that ran across Derousse Ave. and rose to the higher level of the eastbound tracks that cross River Rd. In both 1926 and 1943, this was the fatal site.

In 1926, the train was a very popular means for New Yorkers to escape the city to the fun and leisure of Atlantic City, as has been depicted with some artistic license on the show “Boardwalk Empire.” As spring approached, the demands for seats on the Nellie Bly began to grow, motivating the railroad to add a second “section,” meaning that a second train on the same line would run after the first filled with passengers. On Thursday, April 8, the Nellie Bly ran in two sections, the first with regular engineer William Premble and the second with “extra man” engineer John O’Connor of Jersey City. O’Connor, a father of five, was not a regular engineer on this route, though he had gone over it twice in the previous 30 days.

About 5:27 p.m., the train full of passengers bound from New York to Atlantic City entered the single track curve that would turn it off its southbound course to eastbound. It was running about 12 minutes late. The weather was clear.

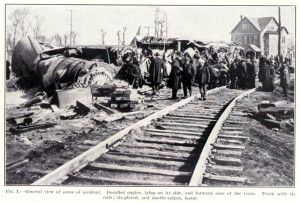

At 5:28 p.m., Mrs. Mary Rainer happened to be absently looking out the window of her home on Derousse Ave. as the train passed. She saw the locomotive suddenly lurch and then tumble to its right, over and off the tracks. Three Pullman cars full of passengers followed the locomotive and tender, crashing into the locomotive and one another. The first Pullman car, christened “Wareham,” struck the rear of the locomotive then rebounded to strike the front of the Pullman car behind it, known as the “Ocean City.” The Wareham swung off the tracks and over on its side. The Ocean City also came off the tracks, but did not tumble over completely, because it came to rest leaning against the locomotive. The third Pullman car, named “Delair,” leaned off the tracks, but did not fall. Reportedly, not a pane of glass was broken in the Delair and injuries on this car were minor.

The locomotive and the first Pullman car took the brunt of the wreck. Then the cries and screaming began.

On the back porch of her home at Derousse Ave. and River Rd., Mrs. Carrie Dole was talking with her daughter, Mrs. Ray Dean, when the accident erupted before them. Mrs. Dole was stunned, but Mrs. Dean immediately ran toward the scene, down the embankment, where she could see that victims of the crash had been thrown through the windows of the passenger car. Calling to her mother for help, she pulled a man with terrible head injuries away from the smashed car. Mrs. Dole followed and brought a pillow, which they placed under the man’s head. The man spoke, saying, “Take me away from here. I am hurt.” Then, he lapsed into unconsciousness and shortly died. His name was William Mentz, a deputy sheriff from the Bronx. He was the only passenger to die that day.

Meanwhile, other local residents rushed to aid the victims. On the platform, Andrew Barber, superintendent of the Kieckheffer Container factory, witnessed the accident and immediately summoned assistance and equipment from the plant. Coincidentally, Pennsauken Chief of Police Cox was passing nearby in an automobile. Quickly arriving at the scene, Cox sent out the call for emergency responders and was answered by not only Pennsauken, but also fire companies and medical personnel from a dozen communities along the riverfront.

The engineer, O’Connor, and his fireman, Anthony Raynkin, were fatally scalded by the escaping steam from the engine. Mercifully, O’Connor was unconscious, but Raynkin suffered terribly. Taken to Cooper Hospital, both died within about two hours.

Among other victims, Lucy Millburn of New York was initially thought to have a fractured spine, but this may have been a result of shock, as she was released within a day with only bruises and lacerations. More serious were the injuries of Charles Richardson, a black Pullman porter, who suffered internal injuries as well as two broken legs. Like most of the injured, he was taken to Cooper Hospital for treatment. The investigative report later indicated that as many as 170 people sustained injury in the derailment.

Among the more lightly injured, Father Joseph McCaffrey, a chaplain of the N.Y.P.D., tended to others more seriously hurt.

An apparently uninjured passenger quoted in the next day’s newspapers had a very different experience of the wreck. Identifying himself as Hollywood film director Victor Halperin, he reportedly described the incident as “one of the greatest thrills I’ve ever had.” Already experienced at filming simulated disasters, Halperin continued his career of mostly “B” movies, including “White Zombie,” starring Bela Lugosi.

Two New York attorneys on the train were quickly quoted in the newspapers as to their belief that the train was moving at an excessive speed, which they were just discussing when the crash occurred. This appeared to cast blame on the deceased engineer. Ethan Wescott of the County Prosecutor’s office appeared to agree, as he closed his investigation on April 9 with that conclusion. In days to come, unidentified railroad men tried to clear O’Connor’s name, noting that he may have applied the brake to avoid the train derailing at the top of the embankment, which would have been far worse.

After the victims had been assisted and removed from danger, and as the smoldering wreckage was examined and conveyed to the Pavonia railroad shops, a crowd estimated at a thousand gathered to view the scene.

In September 1926, the official investigation of the accident revealed that a six-inch section of track had cracked and broken away, probably due to the stress of trains passing at speeds sufficient to surmount the incline up to the level of the eastbound tracks. It was thought that a train that had passed the site nine minutes before the accident had completed the break and that this had caused the fatal accident. It may also be of interest to note that only two days before the accident it was reported that the Pennsylvania Railroad had enjoyed a big increase in revenue in 1925 over 1924, attributed to not only an increase in traffic, but also to “improved economy and efficiency in operations and continued improved expenditures.”

It would be 17 years before the much worse derailment of the Atlantic City to New York passenger train occurred at the same site. In both cases, the community responded immediately and heroically to save and succor the victims. The curving juncture of the two rail routes has long since been removed at Delair, although some of its remnants are still to be seen.

Sources for this column include: contemporary accounts in The Morning Post; and the Interstate Commerce Commission Report of the Director of the Bureau of Safety in re Investigation of an Accident Which Occurred on the Pennsylvania Railroad Near Delair Junction, N.J. on April 8, 1926.